This is the third article in a series for chorus directors and music teams. It is a companion to a video that HU produced in 2016 and a previous article on riser spacing.

Avoid the fight

A natural tendency in choral singing is to compete with the surrounding voices, a tendency called the Lombard Effect. This can be problematic if someone with a “smaller” singing voice stands next to someone with a “larger” voice. Two types of responses are common in this situation:

- The singer with a smaller voice will try to compete with the larger, usually resulting in pressed singing.

- Conversely, a singer with a larger voice may unconsciously pull their voice back.

Effortful singing like this can open a singer up to vocal fatigue and vocal trauma. Neither scenario is what a chorus director wants, which is the best vocal production from each singer.

Various research studies attempted to articulate the most acoustically efficient riser placement (mixed vs sectional, etc.); unfortunately, due to the complex nature of such studies, data from theses studies are tough to rely on.1 There are just too many variables to make these studies replicable. Book chapters with this topic seem to be anecdotal.

So how to place singers on the risers to get the best chorus sound? A safe bet it to use the principles of vocal health and vocal efficiency as a guide. This leads to the concept of voice-matching strategies.

Voice Matching

The first principle to understand behind voice matching is that everyone has a unique and valuable voice. Make sure all understand that no one voice is better than another and the best place to stand on the risers is on the risers.

The second principle is that chorus singers tend to make better vocal choices when surrounded by like-sized, like-timbred voices. There is less competition (Lombard Effect) this way . Many directors have strategies for voice matching, but generally consider:

- vocal fold thickness (check out this video to hear the difference in speech)

- natural larynx height (low laryngeal singing has a generally fuller sound)

- vocal fold closure tendencies (breathy vs. not breathy)

- tongue position tendencies (vowels sung with flatter tongues usually have a duller sound)

Active Listening

A suggestion is to match voices first by section. Line up singers and have them sing something simple enough that they don’t have to think about the notes or the words. For English speakers, the round “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” is easy to use, although really any simple song is fine. (In Sweden I used “Vem kan segla förutan vind” and in Germany I used “Alle meine Entchen.”)

Listen for the unique characteristics of each voice. Begin sorting, pairing, and grouping voices according to the criteria above. The goal is to have a spectrum of voices in the section ordered, generally, light and bright to big and dark. An easy way to do this is number from 1-XX. Then repeat this experience with the whole chorus.

To the risers!

Organizing singers on risers, again, is not an exact science. Generally, use the principles of vocal health and vocal efficiency as a guide. Follow the formula:

- higher-numbered voices should stand behind lower-numbered voices, and

- higher numbers should tend to stand toward the middle.

Listen to the ensemble and verify there are no "hot spots," meaning a voice or a part that sticks out of the sound. This can be done by placing singers by someone of a different voice part as much as possible.

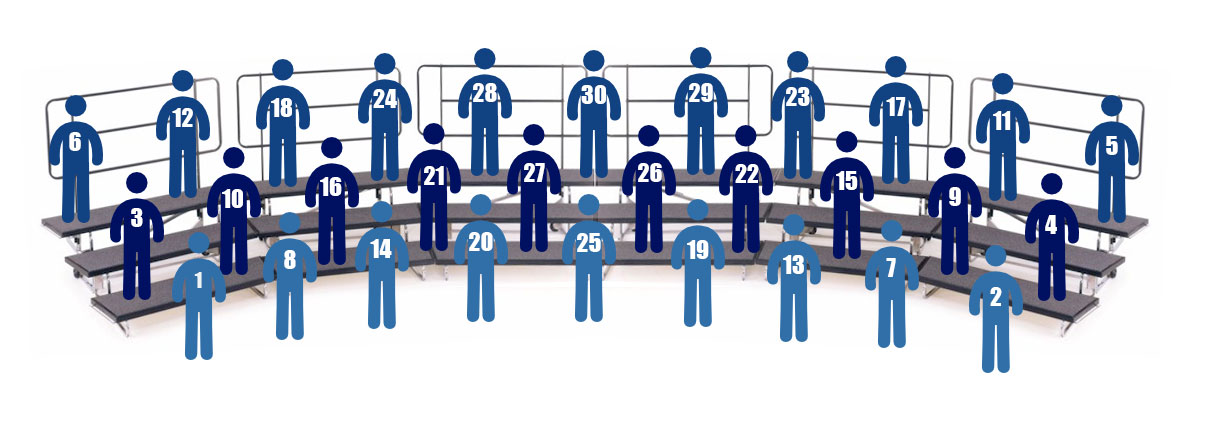

Voice placement of a a 30-singer chorus on risers might look like this

Blend

The word blend has been used for generations as a way to homogenize a chorus sound. The responsibility to blend fell upon the chorus singer. This is problematic because when singers are instructed to “blend,” most assimilate or compromise their voice and make it less efficient acoustically and less efficient in production (affecting the tissues, introducing fatigue).

Directors want their singers to sing with their most efficient, beautiful voice. But asking for blend sends a mixed signal to chorus singers that they can't use their best vocal production or they will stick out. Therefore, the responsibility of chorus blend is the job of the director and the music team, not the individual singer. This is accomplished through voice matching and riser placement.

Employ voice matching strategies to allow them to sing with their fullest, easiest, and most resonant sound surrounded by voices of similar size to achieve balance in the ensemble sound. Increased inter-singer spacing can also reduce the likelihood of pressed singing or competition. It is my recommendation that principles of inter-spacing and voice matching should replace the word blend in our vocabularies.

Other Factors

This article does not suggest that acoustic or physiological factors are the only reasons for riser placement. Music and performance teams should consider how to balance the look of the chorus and performance demands with spacing and riser placement. Additionally, psychological or sociological considerations must be made. For example, some singers feel like they are more efficient when a more experienced voice is guiding them.

Another important factor to consider is the venue in which the chorus sings. For example, the degree to which singers can hear themselves in a given venue can affect their intonation.2 Further, singers have a tendency to raise their larynges (thinner sound) in more absorbent venues.3

Find What Works For Your Chorus

Experiment with your chorus to find the perfect balance of inter-singer spacing and riser placement in a given venue. Remember the goal is to encourage each singer to sing with their healthiest, most resonant singing. These principles reinforce the importance of the Lombard Effect and the Self-to-Other Ratio in choral acoustics.

Enjoy this video of 2017 5th place bronze medal chorus Parkside Harmony, who use a variation of voice matching and riser placement.

Happy, healthy singing, my friends!

1 To understand a scope of available research, see Aspaas, C., McCrea, C.R., Morris, R. J., & Fowler, L. (2004). Select acoustic and perceptual measures of choir formation. International Journal of Research in Choral Singing 2 (1), 11-26.; Daugherty, J.F. (1999). Spacing, formation, and choral sound: Preferences and perceptions of auditors and choristers. Journal of Research in Music Education, 47 (3), 224-238.; Lambson, A.R. (1961). An evaluation of various seating plans used in choral singing. Journal of Research in Music Education, 9 (1), 47-54.; also Tocheff, R.D. (1990). Acoustical placement of voices in choral formations. Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University.

2 Sundberg, J. (1987). The science of the singing voice. Dekalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press.

3 See Ternström S (1989). Acoustical Aspects of Choir Singing. PhD thesis, Dept of Speech, Music & Hearing, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden. The raising of the larynx has the perceptual effect of thinning out the sound or causing it to be more strident. Singers usually raise the larynx by engaging swallowing muscles. These muscles are not required for singing and their use in the same can introduce fatigue into the voice.